I was very fortunate to be the last student to start PhD study with Audrey Holland (University of Arizona). One of the many benefits of studying under Audrey’s tutelage is that she was very “hands off” and encouraged her students to explore new things and to question convention. I found this approach to be liberating and have tried to emulate it with my own PhD students. In spite of this very stimulating environment, I do not remember dwelling much on the question of whether aphasia therapy was a worthwhile endeavor or not. One of my most vivid memories of my time as a PhD student was watching Audrey give grand rounds in the Department of Neurology where she talked about the importance of aphasia therapy, including a recently published meta-analysis by Randy Robey (Robey, 1998, JSLHR). I was certainly aware of negative trials such as Lincoln et al (1984, Lancet) but, looking back, my hunch is that the collective opinion in Audrey’s lab was that, at some level, aphasia therapy is probably helpful.

I don’t recall spending much time pondering the effectiveness question, but we did discuss extensively the difference between impairment-based therapy vs. functional therapy. Although the dichotomy between these two approaches isn’t always clear, I wrote about my perspective on their difference in a paper I am working on along with my colleague, Argye Hillis (Johns Hopkins University).

“There are many different approaches to speech-language therapy for aphasia, with two main camps: Impairment-based approaches focus directly on decreasing the language impairment by targeting the sub-components of language such as phonology, lexical-semantics, or syntax. The goal here is to improve language functions with the assumptions that doing so will generalize to communication abilities and, by extension, communicative quality of life. Functional communication approaches more directly target communication abilities and do not necessarily focus on generalization to reduce speech or language deficits. Rather, these latter approaches are more likely to focus on a relatively small set of stimuli with high personal relevance (e.g. script training). Additionally, this approach emphasizes eliminating communication barriers in the environment, caregiver training to enhance communication, and improving the success of communication rather than reducing impairment.”

I certainly realize that others may disagree with my definitions here, which is not really a problem for what I discuss in the following paragraphs. Regardless of which therapy approach is studied, impairment based or functional, I suspect that most (all?) group studies of aphasia therapy that are properly powered will reveal considerable variance in the outcome across participants. That is, a large proportion of the participants will literally show no changes, or even a decline, in the primary outcome measure. This proportion might be as large as 50%, suggesting that for a positive trial, the overall therapy effect is driven by less than half of the participants. In my opinion, perhaps the most important randomized controlled trial (RCT) of aphasia therapy published so far is Breitenstein et al (2017, Lancet). In short, this RCT showed that speech-language therapy does improve effectiveness of verbal communication measured using the Amsterdam-Nijmegen Everyday Language Test (ANELT; Blomert et al., 1994, Aphasiology) A-scale (Cohen’s d = .58; medium effect size). Moreover, receiving therapy was also related to improved quality of life measured using the Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale-39 (SAQOL-39; Hilari et al., 2003, Stroke), but the effect size was not as large as for verbal communication effectiveness (Cohen’s d = .27, small effect size). Although the type of therapy was described as “combining linguistic and communicative-pragmatic approaches…” (p. 1531), it seems to me that most of the therapy tasks described in the supplementary materials were primarily impairment based with somewhat less direct focus on communicative effectiveness. In any case, personal communication with the lead author, Dr. Caterina Breitenstein, revealed that at least 30% of the participants in their experimental group showed no response to therapy. Based on what I suspect is a typical distribution of outcome data in aphasia therapy studies, I would guess that the Breitenstein et al. trial also included another 10-20% of participants whose response was relatively small compared to the best responders, which means that the overall treatment effect could have been primarily driven by less than half of the individuals in the experimental group.

For the past 4.5 years, we have been conducting a multicenter, cross-over trial with blinded raters of outcome to compare semantically focused therapy to phonologically focused therapy in persons with chronic aphasia (POLAR: Predicting Outcomes of Language Rehabilitation in Aphasia). The primary goal of POLAR is to understand what baseline factors, either neurobiological or biographical, predict individualized response to therapy. Much like “personalized medicine,” a concept with value and importance that is becoming ever more ostensive, we believe that “personalized rehabilitation” should guide the care for every person with aphasia. A part of this approach is to understand why a given person is a good candidate for one kind of therapy and not another. I believe the most effective way to achieve this goal is by conducting large trials where persons with different aphasia severity levels, different patterns of language impairment, and different social needs and desires undergo different kinds of therapy. Then, it will be possible to compare poor and good responders and identify factors that can be used to tailor therapy/management to the next person with aphasia.

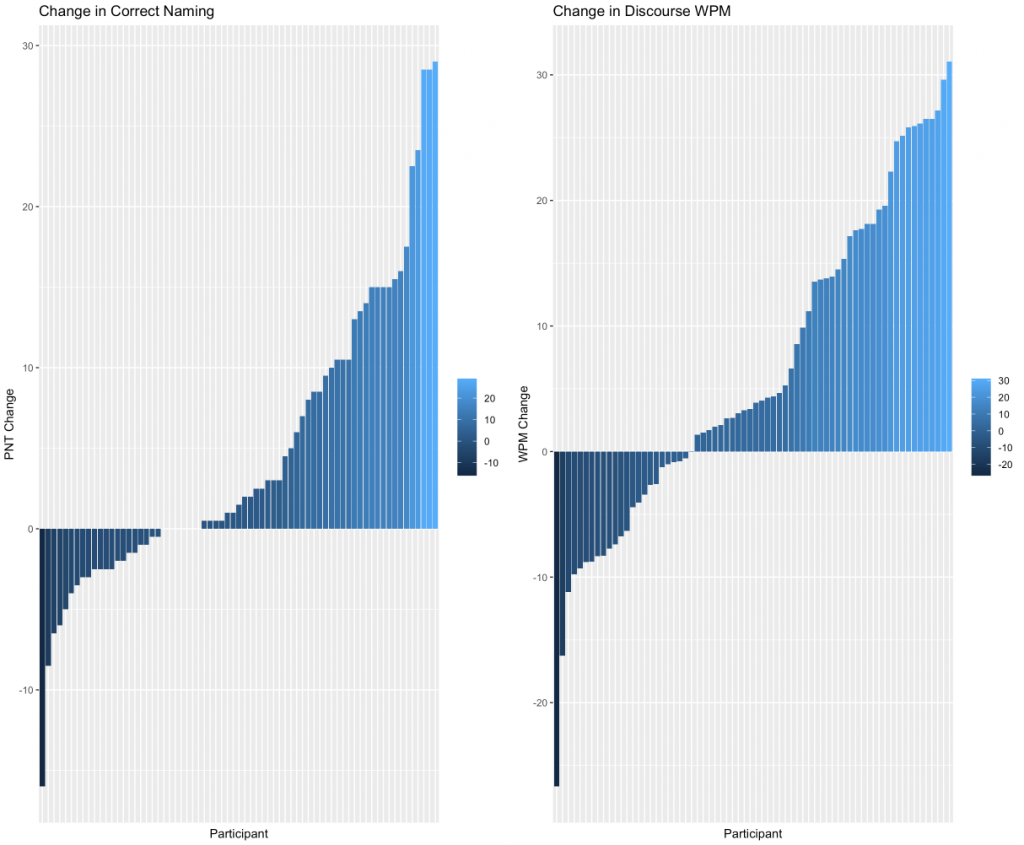

We have three papers in the ‘submitted’ or ‘in preparation’ stage that describe our initial results from POLAR (Lead authors: Alexandra Basilakos [UofSC], Sigfus Kristinsson [UofSC], and Grant Walker [UCI]). We are still collecting data for POLAR and, in the next 1-2 years, plan to publish more comprehensive results. Getting back to the issue of variability in outcome, reading each of these three papers I am struck by the extensive variability in therapy success across individuals and, regardless of outcome measures, I would be surprised if this level of variability was not representative of most large aphasia therapy trials. By extension, I would expect this kind of variability would also be reflected in actual clinical care of persons with aphasia. To demonstrate the variability in therapy outcome, I have included two bar graphs that show changes in correct naming (left) and changes in the number of correctly produced words during discourse tasks (right) at 6-months after therapy completion (figure, courtesy of Alexandra Basilakos). Although there was a statistically significant improvement for both outcome measures, it should be lost on nobody that some of the participants in this trial actually scored worse at the end compared to the beginning. Is it possible that our therapy made them worse? I hope not but suspect our results are very much influenced by intra-individual variability in performance on language tasks that is very common among persons with aphasia. Mixed in with all that variance is a general therapy effect that is statistically significant in the positive direction.

Figure legend: Participants are ordered from left-to-right on the x-axis based on therapy response with ‘decliners’ starting on the left and progressing to ‘improvers’ on the right. The y-axis indicates changes in naming on the Philadelphia Naming Test (Roach et al., 1996, Clin Aphasiol) (left) and different words produced per minute during discourse tasks (right).

One of the things that surprised me about the initial results from POLAR is that there is no correlation between improvements following semantic therapy and phonological therapy. Specifically, individual response to one type of therapy approach was not related to individual response with the other therapy approach. I find this outcome to be very encouraging for several different reasons. For the sake of the current discussion, perhaps the most important point is that type of therapy really matters and that if a person shows a poor response to one type of therapy, try something different! Another important finding is that overall aphasia severity matters for treatment approach, at least of the kind administered in POLAR. Persons with more severe aphasia tended to show worse response to speech and language therapy. This point is further demonstrated in another manuscript we are preparing for publication in which Lorelei Phillip-Johnson (UofSC) did a retrospective analysis of two of our previous therapy studies (Fridriksson, 2010, J Neurosci; Fridriksson et al., 2018, JAMA Neuro; also see Fridriksson et al., 2019, Brain Stim) as well as POLAR data to understand if overall aphasia severity and age are related to aphasia therapy outcome. In all three studies, overall severity predicted therapy response (change in correct naming), with age explaining some significant additional proportion of the variance. More specifically, more severe aphasia and older age indicated poorer response to aphasia therapy. In spite of both aphasia severity and age being significant determinants of therapy response, a considerable proportion of the variance remained unexplained suggesting that other factors probably also play an important role. I will leave it up to the forthcoming papers by Basilakos et al and Kristinsson et al to present the details of our prediction analyses and discuss what factors are most important for positive aphasia therapy response. Once we have completed data collection for POLAR, it is my hope that we can generate a prediction model to aid speech-language pathologists (SLPs) in constructing treatment plans for individuals with aphasia.

So far, much of what I have written, which is mostly in favor of aphasia therapy, contradicts my title that “Aphasia therapy doesn’t work.” So, what gives? My point is that typical aphasia therapy dispensed in the early phases of recovery from aphasia seems highly likely to miss the mark of therapeutic effectiveness and usefulness for the individual patient. Today, there is little agreement among SLPs regarding what factors are most important for determining prognosis of aphasia. A new study by Cheng and colleagues (2020, Int J Lang Commun Disord) queried a group of SLPs (N=54) about what factors they consider most important for arriving at aphasia prognosis (they also asked SLPs what they consider the most important factors for delivering prognostic information to patients). I found the study to be highly informative but was not surprised at the lack of agreement across individual SLPs. Given the dearth of data on this issue, I would have to say that prognosticating in our field is mostly an art, not a science.

As I indicated above, part of the solution to this conundrum is to construct prediction models that can be used to guide the management of individual persons with aphasia. In this context, I think it is important to note that I don’t see such models as being only important for language/communication therapy. Rather, I think that SLPs should be well versed in all approaches that we see as being a reasonable part of the therapeutic arsenal for aphasia: Impairment based approaches, functional approaches, neurobiological approaches (e.g. electrical brain stimulation, if proven effective), life participation approaches, and whatever else that might be reasonable to expect to aid persons who are living with aphasia. Unfortunately, the curriculum for SLP training programs in the USA ensures that the typical graduating SLP tends to be a jack of all trades, master of none, which does not bode well for persons with aphasia who need highly skilled care that takes into account a wide range of knowledge starting from the underlying language impairment to the broad social needs of the individual (sounds like another blog post…).

I am not a fan of artificial dichotomies between individual approaches to treating aphasia. Depending on individualized factors, one person may be best served by focusing mostly on a mixture of impairment based and functional approaches to directly improve their ability to communicate with relatively less focus on life participation approaches to aphasia (LPAA). In this case, that person’s baseline factors may indicate that a given therapy is highly likely to spur significant improvement in communication abilities. In contrast, another person’s baseline factors may predict poor response to direct communication therapy, which may call for greater focus on LPAA.

My speculations here cannot be disconnected from the clinical realities on the ground (at least in the USA) that most persons with aphasia receive far too little therapy and, as importantly, whatever therapy they receive is probably under-dosed, which is a far longer conversation. Nevertheless, I look forward to a time when the work SLPs do with persons with aphasia is primarily guided by sound science and not only by clinical intuition.